the demand for love

Music: The Cure: Wish This week I have avoided SXSW festivities to work on ensuring tenure, which means writing: it's been Joshie Writing Camp (JWC)! At JWC we don't shave, rarely bathe, and eat ready-made. A JWC we read and re-read the reviewers suggestions for revision and try to make everyone happy. Making everyone happy is impossible, of course, when I cannot make myself happy.

Regardless, I've re-written a bunch of stuff for my "Hystericizing Huey" essay, focusing especially on the part that distinguished need, demand, and desire from one another. Here's that part, for the curious (I hope to gosh it makes sense; this is hard stuff to write about):

So what, then, is desire? From the perspective of Lacanian psychoanalysis, desire refers to the unconscious wishes of an individual that, by definition, cannot be satisfied. From a Lacanian perspective, "desire" should be sharply distinguished from its more popular understanding, such as that which is found in the OED: "that feeling or emotion which is directed to the attainment or possession of some object from which pleasure or satisfaction is expected." Lacan's understanding of desire refigures the desired object: with apologies to Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, you can never get what you desire because, if you did, desire would disappear. To better explain this feeling of not getting what you desire, Lacanians often contrast the concept with "need" and "demand." Human need refers to purely biological needs (e.g., for food). Demand refers to a request for something (an object, a deed, a gesture, and so on) from another. As with desire, the distinction between need and demand concerns the status or character of the object, as Joan Copjec elegantly explains:

On the level of need the subject can be satisfied by some thing that is in the possession of the Other. A hungry child will be satisfied by food-but only food. . . . It is on the next level, that of demand, that love is situated. Whether one gives a child whose cry expresses a demand for love a blanket, or food, or even a scolding, matters little. The particularity of the object is here annulled; almost any will satisfy-as long as it comes from the one whom the demand is addressed. Unlike need, which is particular, demand is, in other words, absolute, universalizing. (148)This "universalizing" or formalizing aspect of demand is important, because it underscores why the objects of demand are, in some sense, interchangeable. Demands reflect an emotional drive or push for "something more," insofar the "Other now appears to give something more than just these objects," a something-more that Lacan terms the object-cause or the objet a (Copjec 148-149). In other words, whereas need is satisfied with the production of a specific object, demand represents a partial awareness that the gesture of the person who produces the object is more important. The demand for this something more is the demand for a special kind of recognition: love.

The demand for love is problematic, however, because it mistakenly assumes this "something more" of the Other can be given away. Love, in this sense, is premised on the lie that the object-cause is attainable. For Lacan, "as a specular mirage, love is essentially deception" (Four Fundamental 268). In light of love's deception, "desire" is therefore the word for what is really happening to a subject when she feels that familiar pull of emotion toward an object or another. Desire is the feeling of lacking the presumed objet a and of pulsating around a substitute as the next best thing. For example, sexual desire can be stirred by a partial or part object, like a breast, or a beautiful face, and so on, but one knows very well what the point of sexual desire is not to "get" the breast or the face, but the yearning for this "something more" beyond the breast or the face (see Krips, 22-24). Copjec explains that with desire, "the Other retains what it does not have"--this something-more--"and does not surrender it to the subject." Consequently an individual's desire does not aim toward an object but is caused or inspired by this elusive "something more," this objet a, which the Other refuses to surrender (Copjec 148-149). Again, it is important to underscore that the reason desire is not aiming for a specific object because if that object were attainable, then desire would disappear. Hence desire is ceaselessly metonymic, moving "from one object to the next. . . . Desire is an end in itself; it seeks only more desire, not fixation on a specific object" (Fink 26).

Incorporating these Lacanian notions of demand and desire into the received understanding of emotional appeals expands its explanatory power, but not without some modification. Traditionally, the emotional appeal has been discussed in terms of a rhetor's ability to produce or promise something that the audience wants (Desire-->Object). So, for example, Aristotle suggests that one can enflame an audience's anger through the symbolic destruction of a person (the object) that has insulted or belittled them (Aristotle 124-130). In regard to the demagogue, Kenneth Burke identified emotional appeal working primarily to scapegoat a common enemy (the object) through the processes of identification and division (Burke, Philosophy 191-220). Roberts-Miller notes that "an important goal of the demagogue is to prevent" division among the ingroup by keeping "identification strictly within the ingroup, and to ensure no sense of consubstantiation with the outgroup: 'Men who can unite on nothing else can unite on the basis of a foe shared by all'" (Roberts-Miller 463). In the traditional scapegoating scenario, the object of desire is the destruction or removal of a common foe.

The psychoanalytic understanding of the emotional appeal is different, insofar as desire has no object, but rather, is caused or stimulated by an object or quality (Cause-->Desire). So with Aristotle's example of anger arousal, the target is really a ruse. Understood as stimulus to anger, the desirous appeal to enflame an audience has more to do with the way in which the rhetor's manner, tone, voice, and physical characteristics stimulate their desiring by becoming a cause of, or at least a catalyst for, their desiring. In other words, a rhetor's ability to turn an audience into an angry mob is not achieved by providing a target for their ire, even though the mob believes that the destruction of this target is the object of their passions. Rather, the rhetor him or herself is the cause and the mob identifies with his or her desire to have, for example, a political opponent defeated. Although the rhetor convinces the audience that they really want a given object (Desire-->Object), in actuality, she is the cause of their desiring and the ostensible object is ultimately exchangeable with another (Cause-->Desire).v The psychoanalytic read of scapegoating therefore changes: although hating a common enemy is the end of scapegoating, the source of its appeal in a given rhetorical situation concerns the audience's desire to please the rhetor; the arousal of anger is produced out of love for the rhetor, not hatred of a common foe. The real cause of their desiring is the objet a, which cannot be given. The emotional appeal is therefore fundamentally deception but, with regards to Nietzsche, "in a non-moral sense."

To say that the emotional appeal turns on love's deception is not to say that individuals do not believe that their desire is about a specific object. The ruse object of the emotional appeal is a result of "fixation." Indeed, we can define the emotional appeal as the masquerade of desire in demand, the causation of a fixation. Maintaining persuasion via emotional appeal requires the parade of a series of surrogates that betokens the objet a--otherwise persuasion would cease. Let us take, for example, a self-aggrandizing joke that Huey Long gave before a crowded room of dignitaries as he was readying himself for a run for the White House. In a newsreel that presumably ran in northern state theatres, an opening shot presents Huey speaking in a variety of venues inside a series of bubbles, four smaller bubbles in each coroner of the screen, and a larger bubble in the middle. In the center bubble, Long appears in a tuxedo, smiling. A voice over begins: "Presenting his Excellency, Huey Pierce Long, the dictator of Louisiana, the enigma who is making many Americans regret that the United States ever purchased Louisiana." The screen cuts to the contents of the center bubble; Huey appears in the center screen with his arms behind his back. With a smile and a lilting, southern drawl he says:

I was elected railroad commissioner in 1918 [a small smile]; and they tried to impeach me in 1920 [Long leans forward, a bigger smile appears, but his arms still behind his back; louder laughter from the audience is heard]. When they failed to impeach me in 1920, they indicted me in 1921 [Long leans forward again with a bigger smile, and louder laugher comes from the audience]. And I, when I wiggled through that I managed to become governor in 1928 . . . and they impeached me in 1929 [a big smile appears on Long's face, and there is even louder laughter].In this brief example Long advances a subtle pedagogy of desire in the form of a joke, and its success is measurable in the increasing laughter of the audience at each turn (one can liken this appeal to Freud's famous example of the Fort-Da game, which is mildly similar to the peek-a-boo game one plays with infants; see Krips 22-25). From the audience's perspective, Long will not give his enemies what they want, eluding them at every step, thereby creating a homology between the audience's desiring and the desiring of Long's enemies. Mindful of being labeled a demagogue, Long's embrace of insincerity is signaled by his self-characterization as "wiggling" out of impeachments and indictments, as if he is a kind of lovable outlaw. The pull of the emotional appeal here is not reducible to simple identification-you the audience are like me, Huey, and we share a common foe of "they," as this is the ruse of the emotional appeal. Rather, by hinting at the substitute object of desire-an admission of guilt or a refutation of the changes against him-Long inspires this pull for "something more," for love, tacitly promising he has the power to give something that he does not have. In short: the audience laughs at Long's humor because they love him, or rather, they love the "something more" in him. He functions as the cause of their desiring, and they want to similarly be the objects of his desire.

Today I finally scored me some gnomes for my patio garden. That's right, I got me some gnomes and they were not overpriced. I also picked up a bubbling fountain thing of the

Today I finally scored me some gnomes for my patio garden. That's right, I got me some gnomes and they were not overpriced. I also picked up a bubbling fountain thing of the

Although I would very much enjoy putting together a seminar on the rhetoric of religion (I imagine I would use it as an excuse to teach myself Derrida's later work; we'd start with Augustine and end with The Gift of Death), I would worry about the (my) ethical scaffolding: would the spirit of hospitality—of a respectful agnosticism--really work with a prospective student whom some overheard saying, "I'm just not sure if God wants me to be at the University of Texas." We have some graduate students now who bob and weave in class and assignments (and who they will and will not "take") so as not to offend their religious habits and beliefs. Indeed, I think I'm seeing more of this relgio-graduate identity-building going on than I've ever noticed: they don't understand because they are godless; this is why they need me as a scholar and teacher. Of course, me against the system (or me against obfuscating jargon, or me against the corporate academy, or whatever) is central to the fundamental occultism of the academy, but the righteousness of the inner light has really never felt so emboldened, at least during my brief decade in higher education.

Although I would very much enjoy putting together a seminar on the rhetoric of religion (I imagine I would use it as an excuse to teach myself Derrida's later work; we'd start with Augustine and end with The Gift of Death), I would worry about the (my) ethical scaffolding: would the spirit of hospitality—of a respectful agnosticism--really work with a prospective student whom some overheard saying, "I'm just not sure if God wants me to be at the University of Texas." We have some graduate students now who bob and weave in class and assignments (and who they will and will not "take") so as not to offend their religious habits and beliefs. Indeed, I think I'm seeing more of this relgio-graduate identity-building going on than I've ever noticed: they don't understand because they are godless; this is why they need me as a scholar and teacher. Of course, me against the system (or me against obfuscating jargon, or me against the corporate academy, or whatever) is central to the fundamental occultism of the academy, but the righteousness of the inner light has really never felt so emboldened, at least during my brief decade in higher education. Joy is the word I've been looking for that best describes what we previously termed the "ecstasy of violence" (a term that has lost its shock appeal, here after the video game explosion). Joy is both the word for unbridled (often tearful) happiness as well as an object that causes such happiness (yup, you guessed it: it's the objet a)—as if to say, "you are my joy" (thank you Snow Patrol). The word derives from Old French, of course, as it is also the root of the much afeared jouissance, Barthes term for the texty orgasmatron and Lacan's designated function for the drives. I recognize this is not news, but I am somewhat joyful at having located a word that works for me (of course the pun is intended, just not when I first wrote the sentence).

Joy is the word I've been looking for that best describes what we previously termed the "ecstasy of violence" (a term that has lost its shock appeal, here after the video game explosion). Joy is both the word for unbridled (often tearful) happiness as well as an object that causes such happiness (yup, you guessed it: it's the objet a)—as if to say, "you are my joy" (thank you Snow Patrol). The word derives from Old French, of course, as it is also the root of the much afeared jouissance, Barthes term for the texty orgasmatron and Lacan's designated function for the drives. I recognize this is not news, but I am somewhat joyful at having located a word that works for me (of course the pun is intended, just not when I first wrote the sentence). And my own brand of Joshie algebra brings me to Lacanian algebra, my fear of it, a revise and resubmit summons, and the graph of desire here to the left. In a couple of weeks the psychoanalysis seminar will try to make sense of this graph. Yep. I'm already terrified. But fortunately I did give us three weeks to work through it (and a book long explication of it by Van Haute titled Against Adaptation). I've also got to reckon with jouissance in print, which is something I fear as well.

And my own brand of Joshie algebra brings me to Lacanian algebra, my fear of it, a revise and resubmit summons, and the graph of desire here to the left. In a couple of weeks the psychoanalysis seminar will try to make sense of this graph. Yep. I'm already terrified. But fortunately I did give us three weeks to work through it (and a book long explication of it by Van Haute titled Against Adaptation). I've also got to reckon with jouissance in print, which is something I fear as well. As the nominees for the "best supporting actor" flit across my screen, I'm just finishing up the background reading for tomorrow's seminar on the theory of Carl Gustav Jung. At the behest of a visiting scholar in a couple of weeks, for class I assigned some selections from Anthony Storr's edited collection, The Essential Jung, and I have to admit I'm more than disappointed with Storr's "one-sided"--to borrow a term from Jung--treatment. I've been reading The Cambridge Companion to Jung along with Steven F. Walker's Jung and the Jungians On Myth, and it's clear Storr's presentation suffers from a somewhat willful, custodial blindness to the intimate relationship between Jung and Freud, and the ways in which the homoerotic dynamics of that relationship (roughly a seven year, mutually acknowledged "crush" between the men) found their way into their respective theories.

As the nominees for the "best supporting actor" flit across my screen, I'm just finishing up the background reading for tomorrow's seminar on the theory of Carl Gustav Jung. At the behest of a visiting scholar in a couple of weeks, for class I assigned some selections from Anthony Storr's edited collection, The Essential Jung, and I have to admit I'm more than disappointed with Storr's "one-sided"--to borrow a term from Jung--treatment. I've been reading The Cambridge Companion to Jung along with Steven F. Walker's Jung and the Jungians On Myth, and it's clear Storr's presentation suffers from a somewhat willful, custodial blindness to the intimate relationship between Jung and Freud, and the ways in which the homoerotic dynamics of that relationship (roughly a seven year, mutually acknowledged "crush" between the men) found their way into their respective theories.  For example, the so-called love triangle of Freud, Jung, and Jung's patient Sabina Spielrein is completely neglected (of course, this is one of the topics of Avery Gordan's Ghostly Matters . . . as Juliet Mitchell would note, it makes sense that the Woman is erased by these two . . . in letters), and Jung's horribly botched "experiment" with her goes without mention. Storr is clearly tidying up: this morning I laughed aloud at the assertion that Jung "was no disciple" of Freud. Although it is true that Jung "knew" all along it would end in tears, from his published correspondence with Freud it's obvious he was seeking a father . . . .

For example, the so-called love triangle of Freud, Jung, and Jung's patient Sabina Spielrein is completely neglected (of course, this is one of the topics of Avery Gordan's Ghostly Matters . . . as Juliet Mitchell would note, it makes sense that the Woman is erased by these two . . . in letters), and Jung's horribly botched "experiment" with her goes without mention. Storr is clearly tidying up: this morning I laughed aloud at the assertion that Jung "was no disciple" of Freud. Although it is true that Jung "knew" all along it would end in tears, from his published correspondence with Freud it's obvious he was seeking a father . . . .

It is the dreaded "day after" the Spanish Town Mardi Gras, made worse (we predicted) because it rained the entire day. Indeed, it DID rain on our parade, however, this did not damper the unstoppable spirit of blasphemy and unbridled joy: beads were flung with abandon (as well as

It is the dreaded "day after" the Spanish Town Mardi Gras, made worse (we predicted) because it rained the entire day. Indeed, it DID rain on our parade, however, this did not damper the unstoppable spirit of blasphemy and unbridled joy: beads were flung with abandon (as well as  Today, however, is hangover helper day: there is always a price to pay for drinking all day beginning at 9:00 a.m. Today I do not feel too horrible (always stick to sugarless alcohol, I say, on marathon drinking days), but I know a lot of those mimosa slurpin' hotties may feel a little death: the screaming

Today, however, is hangover helper day: there is always a price to pay for drinking all day beginning at 9:00 a.m. Today I do not feel too horrible (always stick to sugarless alcohol, I say, on marathon drinking days), but I know a lot of those mimosa slurpin' hotties may feel a little death: the screaming  Today shall be spent (a) waiting for the plumber as a consequence of a series of minor plumbing malfunctions (the consequence being no hot water—indeed, no water at all—and the unflushable and unsightly guest turd); (b) grading; (c) writing/reading Agamben. Regarding the parenthetical turd of (a), I am convinced that "naked life" finds a representative anecdote—or perhaps, a token remainder. Isn't it curious in the mad rush to combat naughty dualism and embrace "body" that the dirtier aspects of continental are not written about in our "importation" . . . .

Today shall be spent (a) waiting for the plumber as a consequence of a series of minor plumbing malfunctions (the consequence being no hot water—indeed, no water at all—and the unflushable and unsightly guest turd); (b) grading; (c) writing/reading Agamben. Regarding the parenthetical turd of (a), I am convinced that "naked life" finds a representative anecdote—or perhaps, a token remainder. Isn't it curious in the mad rush to combat naughty dualism and embrace "body" that the dirtier aspects of continental are not written about in our "importation" . . . .  Ken, I like the formulation that naked life is "life that is the ground of its own worth, which is it say not much worth, actually," which I take to mean without bios, which provides the measure. It's my understanding that Agamben takes the "side" of naked life (or at least forwards it as the underdog to champion) from necessity as a result of the cleave forged by sovereignty. Lil'rumpus was worried about my term "madness," which Tremblebot discerned as my tendency to shunt this through some reference to the Lacanian real. Where I was then going to transition (somehow) is to the homological relation of the homo sacer to the sovereign and a gloss of Agamben's comparative reading of Benjamin and Schmitt. As I gather (I haven't read that chapter in months) Agamben suggests Schmitt and Benjamin were (loosely) in dialogue, and the disagreement involved this locus of anomie: is it containable or circumscribed by the juridical (Schmitt), or is there some powerful, explosive, uncontainable "pure violence" (a sort of disembodied, or multi-bodied rather) that Benjamin said was outside of the juridical but that could be harnessed for political change (revolution). I need to get the language of this disagreement more precise, but as I understand it the argument hinges on a dialectical relation between the law and violence—where the law is understood as an instituting and regulating structure (e.g., the father function in Lacan-o-speak) and "violence" is disruptive, uncontainable, er, energy or life-force or, well, death-drive or aggression. Held in tension the currently "political system" works quite effectively, but when they are caused to collapse Agamben suggestions that "the political system transforms into an apparatus of death." By madness I mean mania in that Greek sense (I've been reading Plato, you see): chaotic ecstasy that can lead to beauty as much as harm—the ecstasy of belonging that can lead to joyful murder. I tend to think of a film like War of the Worlds, a violent and exciting tantrum, and serving up a celebration of the apparatus of death promised my collapse of the norm into the exception.

Ken, I like the formulation that naked life is "life that is the ground of its own worth, which is it say not much worth, actually," which I take to mean without bios, which provides the measure. It's my understanding that Agamben takes the "side" of naked life (or at least forwards it as the underdog to champion) from necessity as a result of the cleave forged by sovereignty. Lil'rumpus was worried about my term "madness," which Tremblebot discerned as my tendency to shunt this through some reference to the Lacanian real. Where I was then going to transition (somehow) is to the homological relation of the homo sacer to the sovereign and a gloss of Agamben's comparative reading of Benjamin and Schmitt. As I gather (I haven't read that chapter in months) Agamben suggests Schmitt and Benjamin were (loosely) in dialogue, and the disagreement involved this locus of anomie: is it containable or circumscribed by the juridical (Schmitt), or is there some powerful, explosive, uncontainable "pure violence" (a sort of disembodied, or multi-bodied rather) that Benjamin said was outside of the juridical but that could be harnessed for political change (revolution). I need to get the language of this disagreement more precise, but as I understand it the argument hinges on a dialectical relation between the law and violence—where the law is understood as an instituting and regulating structure (e.g., the father function in Lacan-o-speak) and "violence" is disruptive, uncontainable, er, energy or life-force or, well, death-drive or aggression. Held in tension the currently "political system" works quite effectively, but when they are caused to collapse Agamben suggestions that "the political system transforms into an apparatus of death." By madness I mean mania in that Greek sense (I've been reading Plato, you see): chaotic ecstasy that can lead to beauty as much as harm—the ecstasy of belonging that can lead to joyful murder. I tend to think of a film like War of the Worlds, a violent and exciting tantrum, and serving up a celebration of the apparatus of death promised my collapse of the norm into the exception.

Agamben, however, is not clear, and I'm getting all confused about "bare/naked life" (zoe) and bios or the life qualified by morality and socius. Or rather, I think I get this stuff, I just don't know how to transition from Rousseau's notion of popular sovereignty to Agamben's horrific re-reading of Schmitt. Any of you Agamben fans out there want to give me their slang-style definition of "naked life" in relation to the sovereign? I'll gladly steal it.

Agamben, however, is not clear, and I'm getting all confused about "bare/naked life" (zoe) and bios or the life qualified by morality and socius. Or rather, I think I get this stuff, I just don't know how to transition from Rousseau's notion of popular sovereignty to Agamben's horrific re-reading of Schmitt. Any of you Agamben fans out there want to give me their slang-style definition of "naked life" in relation to the sovereign? I'll gladly steal it.

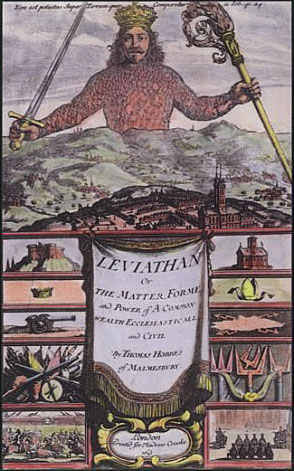

I have been reading the work of Melanie Klein, and work about the work of Melanie Klein, all day—in between phone calls and chat sessions, that beloved and bemoaned labor of love (and Klein is appropriate here, as there is some attempt to render and restore my relation to my mother and my girlfriend, in the same day, via the mediation of the gadget). I have only known Klein from the sound bashing she gets from Lacan, and so I was somewhat excited to read this material with "an open mind." I must admit it's fascinating reading, not only because her ideas are plausible (her vision of the traumatic and barren, somewhat Hobbsian state of nature that is infantile fantasy is as captivating as it is abhorrent, and abhorrent because it rings of truth), but because so much ideological work is being done through the vehicle of theory, presumably in the name of pragmatics. Klein, known for pioneering (along with her enemy Anna Freud) psychoanalytic work with children, also marshaled somewhat of a proto- or pre-feminist scholarly front against the boys club that was psychoanalysis in Vienna and Berlin—at the level of ideas, of course, but also at the level of writerly style

I have been reading the work of Melanie Klein, and work about the work of Melanie Klein, all day—in between phone calls and chat sessions, that beloved and bemoaned labor of love (and Klein is appropriate here, as there is some attempt to render and restore my relation to my mother and my girlfriend, in the same day, via the mediation of the gadget). I have only known Klein from the sound bashing she gets from Lacan, and so I was somewhat excited to read this material with "an open mind." I must admit it's fascinating reading, not only because her ideas are plausible (her vision of the traumatic and barren, somewhat Hobbsian state of nature that is infantile fantasy is as captivating as it is abhorrent, and abhorrent because it rings of truth), but because so much ideological work is being done through the vehicle of theory, presumably in the name of pragmatics. Klein, known for pioneering (along with her enemy Anna Freud) psychoanalytic work with children, also marshaled somewhat of a proto- or pre-feminist scholarly front against the boys club that was psychoanalysis in Vienna and Berlin—at the level of ideas, of course, but also at the level of writerly style I resolved for the new year that I would visit all of the Blue Lodges in downtown and "move my letter" from my

I resolved for the new year that I would visit all of the Blue Lodges in downtown and "move my letter" from my  As a fraternity that is at least 200 years old, one would expect Masonry is not always "up with the times," and so I was not surprised to hear the secretary of the lodge tell me to "bring a lady-friend" for a special, Valentine's dinner. So I had a

As a fraternity that is at least 200 years old, one would expect Masonry is not always "up with the times," and so I was not surprised to hear the secretary of the lodge tell me to "bring a lady-friend" for a special, Valentine's dinner. So I had a  Speaking of happy, I picked up the new Cat Power album, The Greatest, on Tuesday, and I am so pleased! I have always liked Chan Marshall's work—but usually when I was drunk. It was such a bummer to listen to sober. The Greatest is "draggy," as my mother would say, but compared to her other albums one could say it is downright cheerful! The song writing is very strong, the lyrics, often biting, but overall the tone is hopeful. It feels at times like a much less Pollyanna Nora Jones, but with more of a funky-middle-class feel. I like the song "After it All" the best so far, punctuated as it is with gentle whistles. Three cheers for therapy and Prozac! If only Zwan sounded as good . . . .

Speaking of happy, I picked up the new Cat Power album, The Greatest, on Tuesday, and I am so pleased! I have always liked Chan Marshall's work—but usually when I was drunk. It was such a bummer to listen to sober. The Greatest is "draggy," as my mother would say, but compared to her other albums one could say it is downright cheerful! The song writing is very strong, the lyrics, often biting, but overall the tone is hopeful. It feels at times like a much less Pollyanna Nora Jones, but with more of a funky-middle-class feel. I like the song "After it All" the best so far, punctuated as it is with gentle whistles. Three cheers for therapy and Prozac! If only Zwan sounded as good . . . . THE DEL MCCOURY BAND: the company we keep. This is one of the absolute best bluegrass/rock fusion (thought mostly bluegrass) out in the past year. My rule is: if you download more than three songs and listen to them constantly, then you must buy the album. It's an ethics thing I have about stuff on minor or small labels. The album is freakin' awesome, by the way.

THE DEL MCCOURY BAND: the company we keep. This is one of the absolute best bluegrass/rock fusion (thought mostly bluegrass) out in the past year. My rule is: if you download more than three songs and listen to them constantly, then you must buy the album. It's an ethics thing I have about stuff on minor or small labels. The album is freakin' awesome, by the way. A=HA: Analogue. I think it was David Terry who told me the new a-Ha album was the shit, and as a self-professed BIGGEST FAN EVER of synth-pop, I couldn't resist that endorsement. It's not domestically released, but, the import of Analogue is still rather cheap. This is a great pop album (it reminds me at times of the new Coldplay, and at others, of Indochine's Paradize album). Great, solid pop with catchy harmonies and smart pop lyrics. Why Madonna makes it big and real talent like these dudes do not is beyond me. I guess CRAP is shinier, even in sonata form (not that I don't appreciate crap; it's just a shame the chorus of songs like "Cosy Prisons" or "Analogoue" will never be heard by Americans).

A=HA: Analogue. I think it was David Terry who told me the new a-Ha album was the shit, and as a self-professed BIGGEST FAN EVER of synth-pop, I couldn't resist that endorsement. It's not domestically released, but, the import of Analogue is still rather cheap. This is a great pop album (it reminds me at times of the new Coldplay, and at others, of Indochine's Paradize album). Great, solid pop with catchy harmonies and smart pop lyrics. Why Madonna makes it big and real talent like these dudes do not is beyond me. I guess CRAP is shinier, even in sonata form (not that I don't appreciate crap; it's just a shame the chorus of songs like "Cosy Prisons" or "Analogoue" will never be heard by Americans). Platonic righteousness for "the Truth" was displayed for all, as Oprah followed the "redemption" script, crucifying herself for misleading millions and making Frey into a national Judas. Again, Oprah retreats to the individualism of redemption in lock-step with the therapeutic fantasy that localizes all goods and ills in the bosom of the singular individual: "I feel that you conned us all." I was delighted to see Oprah's embarrassment, and the only thing that keeps me from calling for her demise a second time in the blogosphere is that she stayed mad and did not venture forth at the end with the love of forgiveness. No agape here! Just unbridled eros, the violence of redemption made so starkly plain by Mel Gibson in The Passion of the Christ.

Platonic righteousness for "the Truth" was displayed for all, as Oprah followed the "redemption" script, crucifying herself for misleading millions and making Frey into a national Judas. Again, Oprah retreats to the individualism of redemption in lock-step with the therapeutic fantasy that localizes all goods and ills in the bosom of the singular individual: "I feel that you conned us all." I was delighted to see Oprah's embarrassment, and the only thing that keeps me from calling for her demise a second time in the blogosphere is that she stayed mad and did not venture forth at the end with the love of forgiveness. No agape here! Just unbridled eros, the violence of redemption made so starkly plain by Mel Gibson in The Passion of the Christ.  Freud said that his The Interpretation of Dreams was his most inspired and important work, comparing its writing to Jacob's tussle with an angel while confiding to a friend, admitting on some level that the angel may in fact have been the heavenly outlier. At the age of 44, Freud had met one professional failure after the next. He longed for recognition. He had delayed The Interpretation for a year so that it would be published in 1900, thinking that the book was going to make an impact--a turn-of-the-century kind of impact.

Freud said that his The Interpretation of Dreams was his most inspired and important work, comparing its writing to Jacob's tussle with an angel while confiding to a friend, admitting on some level that the angel may in fact have been the heavenly outlier. At the age of 44, Freud had met one professional failure after the next. He longed for recognition. He had delayed The Interpretation for a year so that it would be published in 1900, thinking that the book was going to make an impact--a turn-of-the-century kind of impact. Let us begin at the ending of Freud's "dream book," and more specifically, with the dream of the burning child. Interestingly, Freud chooses to open his closing chapter with mourning dream (p. 547; Strachey trans.):

Let us begin at the ending of Freud's "dream book," and more specifically, with the dream of the burning child. Interestingly, Freud chooses to open his closing chapter with mourning dream (p. 547; Strachey trans.): The realization begins, of course, when he happens upon his wife sleeping. As with the original telling of the burning child dream, the roles only get reversed in the presence of woman, who is the source of truth (this is a metaphor well worn by Nietzsche and something we'll encounter again with Kristeva and Irigaray). In her sleep--that is, in the dream state--she questions the father in a reproachful tone: "Why Malcolm? Why did you leave me?" The ghost is called to account for himself, as if being interpellated by the living, but now we are in his dream. In the film, as with Freud's dream book, the primary identification is with the good doctor, but unlike Freud, this dreamer is revealed to be a ghost--he understand that he is fundamentally a void made meaningful by fantasy. "I see people. They don't know that they're dead," says the boy. When the doctor asks him when he sees dead people, the child responds, "All the time. They're everywhere. They only see what they want to see." So we should ask, in the Zizekian stylistic, "Isn't this Freud's fundamental teaching?" All of us are fundamentally empty, filled up with cultural scripts and narrative and meaning--with all those fantasies of waking life. And isn't the unfolding of the entire film akin to the dream work, the condensation and displacement of the painful and brutal truth that opens the film . . . a scene, incidentally, that the spectator conveniently and perfectly forgets until the end of the film, when the Dr. properly interprets all the pieces of this rebus? Let us not forget that the Dr. Crowes' death was at the hands of suicidal boy returned to punish the father for not seeing that he was burning up on the inside. Mourning always seems to entail a degree of guilt, and death, a punishment.

The realization begins, of course, when he happens upon his wife sleeping. As with the original telling of the burning child dream, the roles only get reversed in the presence of woman, who is the source of truth (this is a metaphor well worn by Nietzsche and something we'll encounter again with Kristeva and Irigaray). In her sleep--that is, in the dream state--she questions the father in a reproachful tone: "Why Malcolm? Why did you leave me?" The ghost is called to account for himself, as if being interpellated by the living, but now we are in his dream. In the film, as with Freud's dream book, the primary identification is with the good doctor, but unlike Freud, this dreamer is revealed to be a ghost--he understand that he is fundamentally a void made meaningful by fantasy. "I see people. They don't know that they're dead," says the boy. When the doctor asks him when he sees dead people, the child responds, "All the time. They're everywhere. They only see what they want to see." So we should ask, in the Zizekian stylistic, "Isn't this Freud's fundamental teaching?" All of us are fundamentally empty, filled up with cultural scripts and narrative and meaning--with all those fantasies of waking life. And isn't the unfolding of the entire film akin to the dream work, the condensation and displacement of the painful and brutal truth that opens the film . . . a scene, incidentally, that the spectator conveniently and perfectly forgets until the end of the film, when the Dr. properly interprets all the pieces of this rebus? Let us not forget that the Dr. Crowes' death was at the hands of suicidal boy returned to punish the father for not seeing that he was burning up on the inside. Mourning always seems to entail a degree of guilt, and death, a punishment.